Chris von Wangenheim Out-Edged Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin.

There was a sea change in fashion photography in the seventies. What had been polished, bright, and straightforwardly glam gave way, in that decade, to a darker tone. Chris von Wangenheim’s work exemplified the new mood: Alongside his (now) more- famous peers Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, von Wangenheim drew sex, violence, and irony to the surface of fashion imagery, shooting eyebrow-raising editorials for the likes of Vogue and Interview and equally provocative campaigns for houses such as Valentino and Christian Dior. Von Wangenheim’s career was brief—he died in an automobile accident in 1981—but his oeuvre’s mix of perversion and sheen continues to assert an outsize influence. Steven Klein is one ardent fan, and he provided the foreword to the new book Gloss (Rizzoli), the first complete monograph of Von Wangenheim’s work. “Chris’s work doesn’t shock me,” says Roger Padilha, who coauthored the book with his brother, Mauricio. “But it does haunt me. His photos have tremendous staying power.” Here, Roger and Mauricio talk about Von Wangenheim and why his risqué photos deserve to be seen afresh.

To the extent I was familiar with Von Wangenheim before I paged through Gloss, it was because I’d come across some of his most notorious images, like the campaign for Dior with Patti Hansen standing by a burning car. So I was surprised to find that his early photos, like the editorials he produced for Anna Piaggi at Italian Vogue, were actually pretty chipper. What do you

think accounts for his shift in tone?

ROGER PADILHA: I think he reacted to what was going on around him. He moved to New York just before the seventies, and although it’s hard to remember now, the city was really seedy back then. It felt dangerous. I mean, it was also very glamorous—you had Warhol’s whole scene and all that—but there was always the threat of violence.

MAURICIO PADILHA: Think about the blackout, the riots . . .

RP: Yeah, and what we found, in fact, going back through the archives, was that we could line up the dates of photos with events going on at the time. Like the blackout, for example, or like when Deep Throat was showing at theaters in Times Square. He was really reflecting and interpreting his environment.

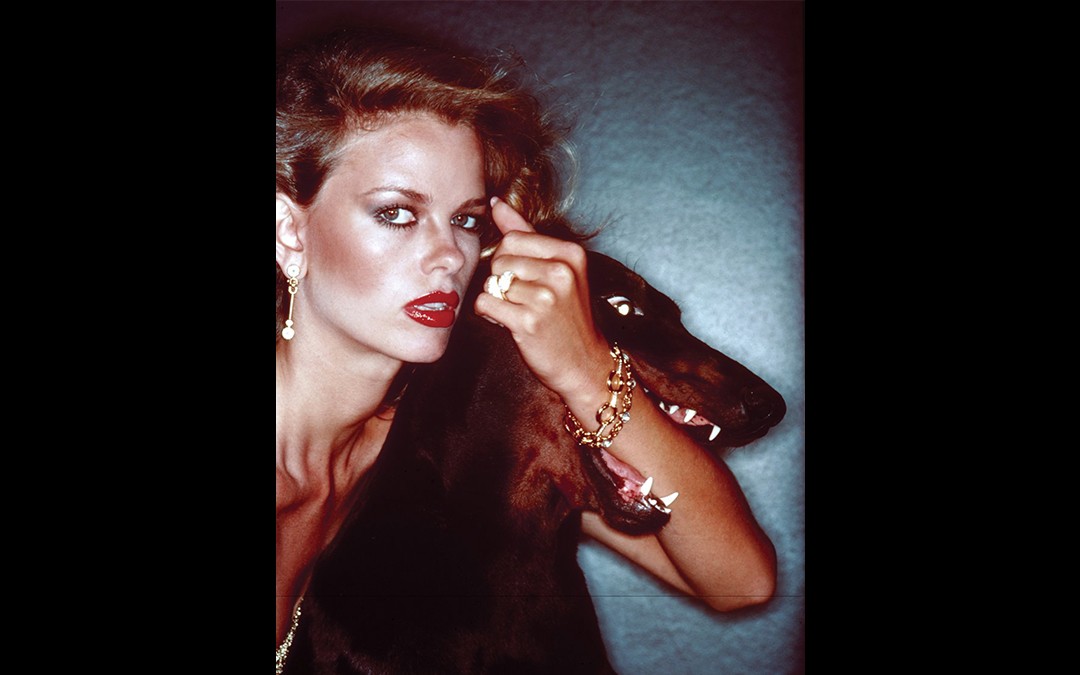

How on earth did he get away with doing those outré shoots—like the one with Christie Brinkley getting bitten by a Doberman—for a magazine like Vogue?

RP: Grace Mirabella was editing Vogue back then, and what she told us was that the subversiveness of what he shot was matched by the sheer technical accomplishment of his craft as a photographer. He was just very, very good. But—yeah, to your point, when we went back through the magazines and looked at the work in context, I mean, it’s shocking. Imagine opening up a Spiegel catalog and finding a Steven Klein shoot. It’s like that.

But then again, it’s not like Chris von Wangenheim was the only photographer pushing those buttons back then; that was also the heyday of Bourdin and Helmut Newton’s breakthrough era. Why do you think Von Wangenheim’s reputation has been so eclipsed by theirs?

RP: A lot of it does come down to the fact that he died relatively young. And his wife— the model Regine [Jaffry]—who had the rights to his work, was more consumed with raising their daughter than establishing his legacy. But when he was alive and working, he was as busy and as famous as Bourdin and Newton.

MP: And his reputation has definitely survived among photographers. Steven [Klein], Mert & Marcus, Terry Richardson—they all told us what an inspiration he’d been to them. They saw those images as kids and they remembered.

Given that Von Wangenheim trafficked in similar themes to Newton and Bourdin, how would you describe what made his work feel so different from theirs?

RP: The way we like to think of it, Helmut Newton’s work has a sense of foreboding, like something’s about to happen, and Bourdin is more crime scene–y, as though the thing has already taken place. With Chris von Wangenheim, you’re right in the middle of the action. It’s in-the-moment.

This book is seriously NSFW. It’s tempting to call a lot of these images pornographic—except there’s something so clinical about the way Von Wangenheim shoots, you feel like someone would have to be very off to be turned on.

RP: It’s a hard thing to wrap your head around, what exactly gives his sexual images such a sense of coldness. I think, in part, it’s because he liked to use models that had a kind of coldness to them. And when you pose those models on brushed silver floors, there is a surgical quality. His pictures are also sort of voyeuristic, and that, plus the models—it adds up to this quality of unattainability, which is what takes the sexuality out of a porn context and makes it right for fashion.

MP: He was painting a picture. And the model was an object within the picture.

Most of the overtly sexual images in this book are outtakes from shoots, like the nudes of Gia Carangi behind the chain-link fence. Was that a typical practice for Von Wangenheim? He’d wrap the stylist, send back the clothes, and get the models to strip off and keep shooting?

RP: Pretty much. Those Gia images, they were shot after they’d wrapped a shoot with her in streetwear, like, a bomber and a pair of jeans. But I think what he liked about working with someone like Gia was, it wasn’t hard to get her to do the crazy stuff. She was actually living in a subversive way—she hung out at CBGB’s, she dated girls—and that’s what he wanted to capture, in the most immediate way possible. It’s like, Gia naked behind a chain-link fence, making out with a woman—that’s probably not far from the truth of what she’d have been doing that night, anyway.

Speaking of nudity. . . . For a fashion photographer, Chris von Wangenheim

did not seem to be overly concerned with, you know, clothes. Or selling them.

RP: It’s true that he wasn’t so interested in clothes. I mean, he got sent to Europe once to shoot the couture collections, and the photos he came back with are of two women naked on a bed together, with dresses hung up behind them. But he understood that what he was selling wasn’t the clothes—it wasn’t, “Oh, look at that great coat, I’d like to own that.” He was selling an allure. He was very, very good at creating these situations that seemed strange and somehow out of reach but that you’d like to be a part of.

Did you get the impression that the models liked working with him?

RP: Well, he was married to one of them. And all the models we spoke to, like Christie Brinkley, for example, they all said, yes, he’d put us in these awkward positions, but he

really loved women. And he’d work with the same models again and again.

That dark mood in fashion photography that Von Wangenheim helped to establish was on the wane when he passed away. How do you think he’d have reacted to the sunnier tone of the eighties? Would he have changed course? Or was the darkness baked-in with him?

MP: My guess is he would have found a way to adapt. I mean, he was a great observer of that dark world around him, in the seventies, but no one we spoke to described him as a dark person. They all said he was a workaholic. He’d hang out at places like Max’s Kansas City or with the Warhol crew, but he didn’t party. He was just taking it in.

RP: We came across an interview with Chris, from shortly before his death, where he said, “I’m moving in a different direction. I’m not doing images like this anymore.” Who knows why he said that—he’d just become a father, maybe that had something to do with it?—but it seems like he was ready to move on. And he would have had to, because the seventies, you know, they just ended.

MP: The AIDS epidemic, Reagan—

RP: Studio 54 shut down . . . It was like, okay, done. It would have been interesting to see how he’d bring his aesthetic to what was going on around him in the eighties, which just felt so, so different. And I’d really love to have seen what he would have made of our celebrity culture today. I’m sure he would have had something very interesting to say.